Dumitru Nistor, a peasant from the village of Nasaud, was born in 1893

Dumitru Nistor, a peasant from the village of Nasaud, was born in 1893.

His childhood dream was to travel and see foreign countries, so in 1912, when the time for recruiting came, he asked to be enlisted in the Austro-Hungarian navy, not the Transylvanian militia, where Romanians usually ended up.

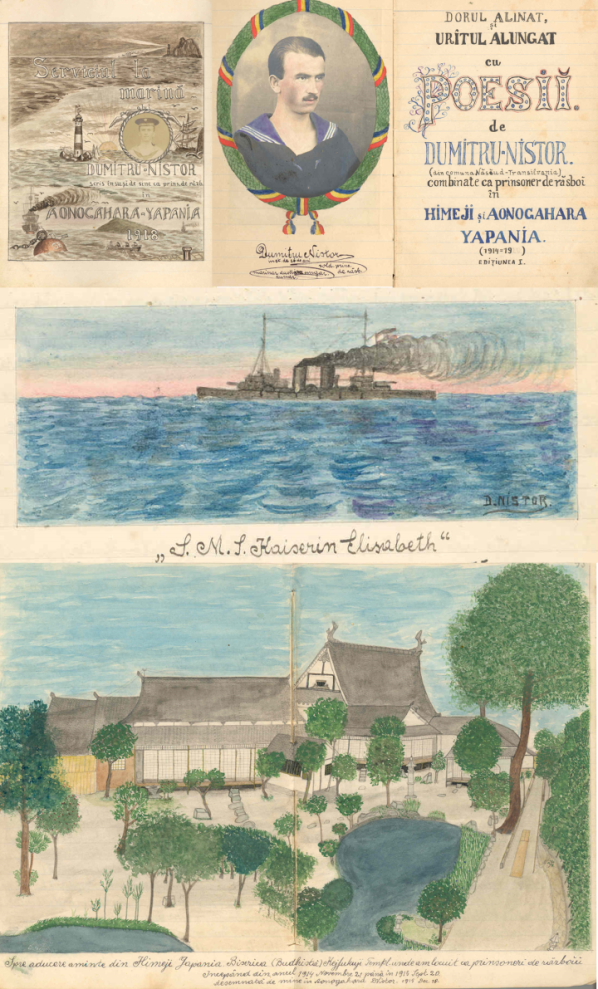

After graduating from his Navy studies, and a trip to Vienna, he embarked as Geschützvormeister ('first cannon pointer') on the ship SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth, destined for Asia. World War I found the SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth battleship in the China Sea, where it took part in several naval battles.

On 2 November 1914, the decision was made to sink the ship. The crew also lost the land battle and Dumitru was made a prisoner by the Japanese and taken to Japan.

For the next ten months, the peasant-seaman from Nasaud remained a prisoner in a Buddhist monastery in Himeji, and was then moved to a prisoner of war camp specially built for German and Austrian prisoners at Aonogahara, not far from Kobe, where he remained until the end of 1919.

To appease his longing for his homeland, Dumitru Nistor began writing during his imprisonment:

'…seeing that I have so much time, I decided I shouldn’t let it go unused. That would have been a horrible shame; (…) That’s why I always kept myself busy with something: writing, reading, drawing, painting, learning new languages etc. I then attempted to unload the weight and pain which tormented me and burdened my heart: but with whom? And to who? (…) Not having anyone to share my pain and ideas with, I thought it good to share them with the paper: it endures, it gives the right and allows everyone.'

Dumitru Nistor's diary, Europeana 1914-1918, CC BY SA

He kept a diary entitled My diary – Dumitru Nistor’s navy service, written by himself as a war prisoner in Aonochara – Japan 1918 and compiled two poetry volumes of poems composed by himself and gathered from his army brethren.

He describes them as 'international songs. Specifically Romanian, Italian, Serbian, Croatian, Slavonic, Bohemian, German and Hungarian songs, as I really loved singing, since I was always a happy person.'

The titles of the volumes are The longing and misery chased away and Youth is life’s flower. Exquisitely beautiful, with charming unique and exotic ink and watercolour drawings, Dumitru Nistor’s volumes are valuable historical documents.

In the chapter The European war, or rather, the Universal war, Dumitru recalls in detail, day by day and hour by hour, the battles fought by the SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth’s crew to defend the German colony of Kiaotcheao.

As an ally of Great Britain, Japan addressed an ultimatum to Germany on 15 August 1914 which went unanswered. As such, on 23 August, Emperor Yoshihito declared war on Germany. On 27 August 1914, a Japanese squadron blocked the port of Tsingtao, and the SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth, despite being an Austro-Hungarian ship, joined the naval battles (after several stutters) as an ally of Germany. Right from the start, the battle appeared hopeless. On 2 November, the decision was made to sink the ship, so as not to let it fall into enemy hands, and the crew disembarked with the battles continuing on land until 6 November.

This is how Dumitru Nistor tells the story of the surrender to the Japanese:

'As the Germans realised that any resistance from our side would be futile, they raised the white flag and surrendered, and us Austrians with them, at exactly 6.30 in the morning. As such, Tsingtau fell to the Japanese on Saturday, November 7th, at 6.30. After surrendering, we laid down our weapons in “Motke Kaserne”, at 7 in the morning. The Japanese minded us and kept us in the barracks’ yard until the evening, without giving us anything to eat. Around us there were now guards with bayonets on their rifles, like traders next to purchased cattle. At night they let us in the barracks to sleep. We slept like logs, as we were so tired after so many sleepless nights. The next day, on November 8th, we woke up at 6 and washed our faces, a very good feeling, as it had been a week since we last did this. After washing, we donned clean clothes. At about 6 in the evening, they took us Austrians to the “Governament Schülle”, where we slept that night. The next day, on Monday, November 9th, we went with the Japanese to the battlefield and gathered up the dead. We were now talking to each other like friends, we were giving each other cigarettes, only the poor dead lied there motionless, they were all crushed by grenades and pierced by bayonets, some had their skulls bashed in and their guts out, with no arms or legs, God forbid, it was horrible to touch them, but what else could we do? We couldn’t leave them there as loot, they were not dogs, they had been our brothers and comrades. In the afternoon we organised a funeral for them with parades, a German priest held a beautiful service, we all shed tears, and then we buried them, we shot three volleys, and the music ended the ceremony. The siege (Belagerung) around Tsingtau had lasted for 41 days, a shameful fact for the Japanese who lingered so much around this small town. They came upon it with 60,000 soldiers, the entire garrison of Himeji, and another 5-6,000 Englishmen, while we poor saps were in Tsingtau about 5,000, cats included. We were 318 Austrians, while the others were Germans.'

Dumitru Nistor returned home in 1920, and lived until the 1960s.

He continued his work as an amateur artist. He compiled a total of 26 manuscript notebooks, but the first three, acquired in 1994 by the 'Octavian Goga' Cluj County Library, are the most valuable.

These documents are a contribution from the Cluj Library to Europeana 1914-1918