Songs were a key part of social life

Whether they had a message or were a simple form of entertainment, songs were a key part of life in society at this the beginning of the 20th century. The songs which would be churned out for popular consumption hailed from a long tradition, stretching back to the Revolution, taking in songwriters such as Béranger and Jean-Baptiste Clément, and they came in all sorts of forms for all sorts of audiences and causes.

Very different in their themes from the traditional religious and children’s songs, the happily-ending romances were the most common on the cabaret stage. Because they were oral by nature, these popular songs were produced and widely heard in the form of very cheap small versions, of which a number took on a new stature from the end of the century by means of illustrations which sometimes bore the signature of great names and which were sold in the street or as a supplement to magazines and daily newspapers. Songs with a social or political message, also lived on, carried by the voices of singer songwriters and contained numerous examples of anticlerical, anarchist and antimilitarist feeling which ran through pre-1914 society.

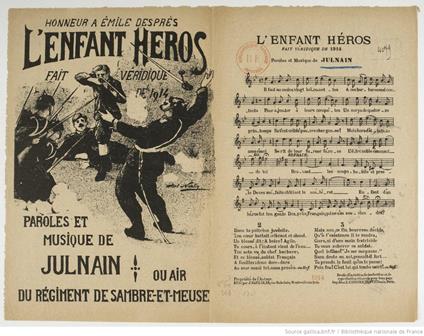

L'enfant Heros. Public Domain, French National Library

L'enfant Heros. Public Domain, French National Library

One may have thought that the First World War, with all its barbarity, might have silenced the songwriters and starved the people of their "thirst for songs". Not at all. Folks would sing on their way to the front, they would sing in the rear echelons, to stoke up their courage, and despite everything else to entertain themselves. Nevertheless there was a hint, through the new and revisited themes, of the hardship that everyone was experiencing. Out of more than 300 small versions of the songs from the Great War kept at the department of Music of the BnF (French National Library), around 70% (215) came out during 1915 alone, compared to 45 in 1914 and 37 between 1916 and 1918.

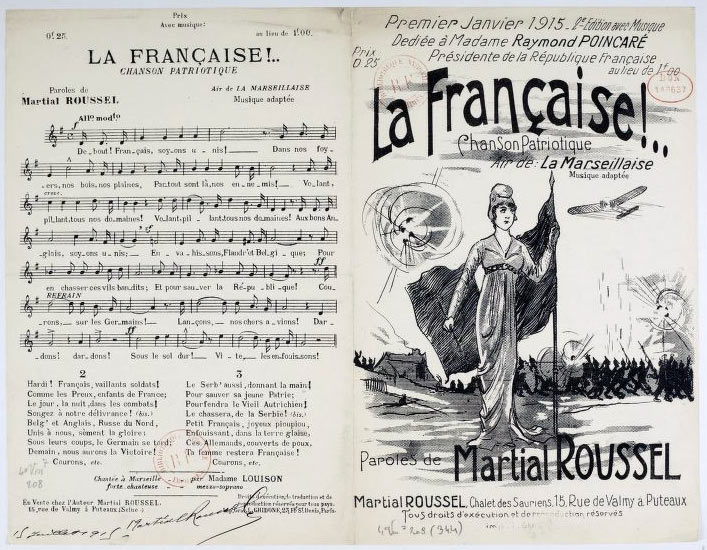

During the two first years of the First World War, patriotic songs enjoyed a major resurgence, similar to that seen after the defeat of 1871. Very popular tunes or lyrics such as the Marseillaise or the revolutionary song, the Carmagnole, were often covered. (La Carmagnole du Kaiser, The Carmagnole of the Kaiser) (La française, sur air de la marseillaise, The Frenchwoman to the tune of the Marseillaise) on the label.

Songs about the defeat of 1871, and the fate of the people from Alsace-Lorraine, such as the famous romance "C’est un oiseau qui vient de France" (A bird which came from France) were adapted in 1914. Public Domain, French National Library

Songs about the defeat of 1871, and the fate of the people from Alsace-Lorraine, such as the famous romance "C’est un oiseau qui vient de France" (A bird which came from France) were adapted in 1914. Public Domain, French National Library

Alongside the national anthems of the allied powers, and the traditional "travelling songs", very many "patriotic songs" which were aimed at uniting the Nation in a tremendous surge of republicanism, bore witness to the principal military movements, in Belgium then in France; the fall of the bastions of Liège and Namur, the siege of Paris and the requisitioning of the taxis for the Marne were recounted with bellicose and vengeful enthusiasm which portrayed the enemy as something to be demonized and ridiculed.

For indeed the "krauts" were accused of being responsible for the worst atrocities throughout the war, such as raping French women and killing children: L'enfant au p'tit fusil de bois, Il est foutu Guillaume!, Gavroche dans la tranchée, Ballade impériale and L'enfant au p'tit fusil de bois

With the war entering a stalemate from the autumn of 1914, the determination and hope for a quick end to the conflict progressively gave way to the harsh reality of the battlefields. References to the dead and wounded would start to appear in the lyrics and on the illustrated covers of the songs which immortalised their contribution to the war. Whilst at the same time, at the Panthéon the talk was of the heroes of Valmy and the Great Army, and even Jeanne d’Arc, to fill the conscripts with the stomach for battle and encourage the youngest to enlist.

Charity work to support the wounded and their families was intensified. From November 1914, with the reopening of the theatres in the rear echelons and the establishment of the army theatres, songs for entertaining started to appear, often full of propaganda or happy sentiments, as an antidote to the boredom experience by the soldiers stuck in their trenches, and as a way of providing them with a form of contact with the rear echelons.

The musicians who were called up or posted to the front such as the songwriter Théodore Botrel or the composer André Caplet, author of the famous Marche de Douaumont (March of Douaumont) would use their talent to help out the Army. The rear echelons were treated to performances of “real-life songs" which played up sentimental or comical emotions, in a popular language which was often rich in colour to the point of containing slang taken from working songs. The musical scores which were more often than not written or composed by amateur authors (60% of them would remain anonymous), would be restricted to a melody without any accompaniment, using known lyrics and tunes.

In the form of choruses and couplets based on polka or marching rhythms, they would be all about the daily life in the trenches, honouring in turn the different arms and jobs from the "poilu" (infantryman) or the “bleuet" (blue uniformed infantrymen of 1915), to the airmen, not forgetting the “chauffards" drivers, the stretcher bearers, the nurses and the health services. The rear echelons were not to be outdone with their long list of stereotypes: French women reduced once more to their traditional role of devoted mothers, sisters and wives, specialist workers called up to the rear echelons to contribute to the war effort in the "cannon and ammunitions" factories.

The bayonet, the machine gun as well as the famous 75mm field gun, which were the soldiers’ faithful companions and the pride of the French army at the start of the war, provided the rhythm to the songs with their noise whereas the love stories and other “three penny romances”, were intended to take the soldiers’ and people’s minds off the horrors of war. The illustrated covers, which were very rarely signed, sometimes set to colour (in the colours of the French flag which was itself very much in evidence) despite these difficult years, were in tune with the language used: the aesthetics just like the melody, which could be serious or for dancing, scholarly or simplistic, rousing or poignant, would fit in with the type of language in the song.

Le Petit Journal. Public Domain, French National Library

Le Petit Journal. Public Domain, French National Library

Alongside what was an "easy" repertoire, there were also lyrics with a high literary and musical content, coming from established authors, from often conservative backgrounds (Charles Péguy, for example), and from professional musicians (Claude Debussy) many of whom performed at concerts on the front line. As varied as they were, these edited songs were none the less the tools of the propaganda machine and were subject to rigorous censorship. This was how the song Les héros de Craonne, (The heroes of Craonne) which was written in 1918 as a tribute to the Paquette division which sacrificed itself on 5 May 1917, was claimed to be the reply to the famous Chanson de Craonne.

Song of Craonne itself was censured because of its subversive nature with regard to the Nation and whose anonymous author was never unmasked despite the rewards which were promised… Although peace was sometimes mentioned, it was because it was to be fought for in a just war "for freedom and the defence of humanity" in 1914, but the peace which was to be earned through a vast Fraternity movement, which implied the refusal to fight, emerged at the end of 1916: "After so much pain, the hatred Will finally give way to Fraternity! No more bloody fighting, no more pointless slaughter, So let mankind live in peace from now on! Chorus … Let the World Fight together as one So that Peace will triumph!" Find the full French song here.