Is there still a place for handwritten diaries in this world of social media?

Today, 6th July, marks the 70th anniversary of Anne Frank’s family going into hiding in their Secret Annex at 263 Prinsengracht, Amsterdam. 13-year-old Anne had been writing her now-famous diary for less than a month. Her work, which has sold over 31 million copies and been translated into more than 65 languages, is a moving account of life for a Jewish family in hiding in the Second World War.

Anne wrote the diary for herself, but in 1944, Gerrit Bolkestein, a member of the Dutch government in exile, announced his wish to collect eyewitness accounts of the Dutch people under the German occupation. Anne decided that when the war was over a book based on her diary should be published. As the enduring nature of Anne’s diary shows, the recording and preservation of people’s life experiences is important. Europeana’s own World War 1 road shows have brought several other war diaries to light, two examples of which are below.

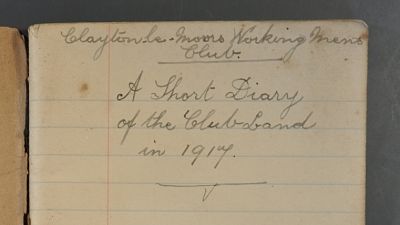

First page of William Monk's Diary, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License

First page of William Monk's Diary, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License

William Monk’s ‘A Short Diary Of The Club Land in 1917’, describes Clayton-Le-Moors Working Men’s Club’s allotment in Preston, England, which was established because ‘the government warned the people of the importance and necessity of the cultivation of all available land in the country’. The journal charts both the challenges of running a group allotment, and the progress of the vegetables, describing, for example, how a snow storm hampered potato sowing, and how bean plants had to be sprayed at midnight in the moonlight.

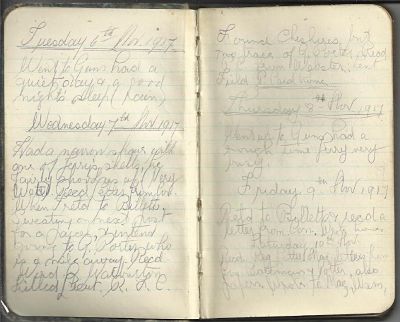

George Lowe's diary entries for 6-8 November 1917, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

George Lowe kept a handwritten diary from November 1917 to May 1918, when he was assigned to a siege battery. The journal begins: ‘I recd this book on 5/11/17. I had already made 2 different attempts to keep a short diary but always neglected them. So I will start from the above date in earnest.’ Just two days later, George writes ‘Had a narrow shave with one of Jerry’s shells, he fairly shook us up.’ The very impulse that drives people to keep diaries is that which makes them valuable to future generations - to record an existence which, particularly in times of war, we realise is only too fleeting.

There are many diaries available in Europeana, some dating as far back as the 11th century . Each of them provides us with a view of a bygone time, in the words of those who saw it for themselves. What would the authors of these decades-old, or indeed centuries-old diaries, think if they knew they could be read by millions in the 21st century? Is there still a place for handwritten diaries in this world of online blogs, shared digital calendars and social media? It is now common practice to publish our thoughts and feelings to a global public instantly. Is the age of the diary over?